Free online translation tools – too good to be true?

Times have changed, and so have machine translation tools. Free online tools such as Google Translate and DeepL (developed by the creators of Linguee) have begun using neural technology to generate much more fluid and idiomatic translations. Just a few years ago, machine translations were something of a laughing stock — but now even language professionals are astonished by the quality they provide.

Neural machine translation (NMT) is a statistic-based method which involves training the translation tool with vast quantities of data (in the source and target languages). Since the big data approach requires significant computing power, it has only recently become possible. The older method of statistical machine translation (SMT) has existed since around the start of the millennium and is based on the frequency distribution of phrases in the training data. In simple terms, it uses the bilingual training data to determine the most likely sentence in the target language. The neural method differs from this approach in that it imitates the neural pathways in the brain using artificial intelligence and deep learning. This means that the connections between the source text and target text are identified by artificial neural networks.

Professional translators increasingly find themselves having to answer the question of whether there’s really a need for human translations any more. At the same time, we as language service providers are exploring whether we can use machine translation to our advantage. But the results of our practical experiments with these tools aren’t nearly as promising as we might have expected at first glance. Below, we’ll take a look at the major challenges involved.

Quality problems

The quality of neural machine translation tools isn’t nearly as reliable as you might think based on how well the translations read. While the grammar might be correct, for example, words or even whole clauses are sometimes omitted, or the meaning is distorted. This is particularly dangerous for machine translation users who don’t have a good command of the source language. But even for language professionals who are post-editing machine translations, the risk of overlooking errors is considerable. So the more important it is for a text to be absolutely accurate (for example, a leaflet in a medication package or an operating manual), the riskier it is to use machine translation (MT), even for highly standardised source texts. Moreover, MT tools are unable to identify errors in the source language, no matter how illogical the text may be as a result. Unlike a human translator, these tools simply have no idea what they are actually translating.

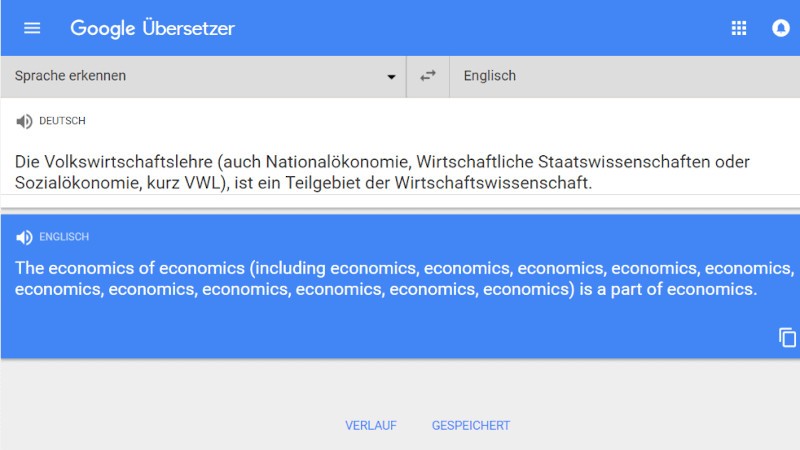

Some of the results can be amusing — take the machine translation of a perfectly legitimate German sentence shown below. But when part of a sentence is left out of a contract or a power of attorney, there can be serious legal consequences.

Data protection risk

Free online translation tools take all the data that is entered into them and store it on their providers’ servers to be used in the future. This means that, under the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), personal or confidential data should never be entered into these tools — that would constitute data processing in accordance with Art. 4 GDPR [1]. The logical extension of this is that you should never use online machine translation tools to translate from a language that you don’t understand at all because, of course, you can’t be sure whether or not the text contains personal data.

The same goes for all copyrighted texts. Entering these texts into Google Translate or other similar MT tools without the consent of the author is a breach of copyright, since the text will then be available to third parties. The fact that Google Translate “trawls the internet for texts that it throws into a vast database for statistic-based MT (including NMT) constitutes a breach of copyright, as it’s safe to assume that the service provider hasn’t systematically asked for permission to use each and every one of these texts.” [2]

DeepL has at least included an explicit warning in its privacy policy: “Please note that you may not use our translation service for any texts containing personal data of any kind.” [3] Google Translate and Bing Microsoft Translator don’t display any such warning to users or inform them what happens with the text they enter and with the resulting translations. The only information available is the general service agreement which applies to the use of the provider’s services. The Microsoft Services Agreement, for example, states under “Your Content”: “When you share Your Content with other people, you expressly agree that anyone you’ve shared Your Content with may, for free and worldwide, use, save, record, reproduce, broadcast, transmit, share, display, communicate […] Your Content. If you do not want others to have that ability, do not use the Services to share Your Content.” [4]

Workload

Machine translations can be improved through post-editing by human translators. Depending on the quality standards that the target text needs to meet, it will undergo either light or full post-editing. Light post-editing involves correcting grammar and spelling, as well as any errors which affect the meaning, but leaving the style and word order untouched even if the sentence sounds strange or unnatural. Even this process can involve quite a lot of work depending on the machine tool’s output. Full post-editing, meanwhile, should result in a target text which is very close or equal in quality to a professional human translation. As a result, this process is much more time-consuming and expensive. The exact types of errors which are to be corrected should be agreed with the client or translation user in advance, since the style of the translation and the use of particular specialist terminology are not equally important for all text types (and readers). Full post-editing can ultimately involve more work, and therefore higher costs, than a (new) translation by a qualified language service provider.

It’s also important to bear in mind that post-editing does not count as revision (proofreading) by a second translator in accordance with ISO 17100, the standard for translation services and quality management in translation companies. Revision would be a separate step carried out after post-editing. So the overall work involved in editing a machine translation can be significant. It’s also hard to predict due to the highly variable quality of MT — it depends on the subject area and, of course, on the quantity and quality of data used to train a machine translation tool for that particular subject and language combination. In any case, the language combination has a major impact on the quality of machine translations, as there are not enough data available for uncommon language pairs to properly train machine translation tools.

Expertise required

The ISO 18587 standard for “Post-editing of machine translation output” requires post-editors to have a university degree either in translation itself or with a significant focus on translation, or alternatively a different university degree combined with relevant professional experience. Post-editors without a university degree must have professional translation or post-editing experience equivalent to five years’ full-time work in order to meet the standard. Other ISO criteria include technical, cultural and subject-specific expertise as well as strong research skills and the ability to find and process information with ease. Post-editors also need to have general knowledge of MT technologies and the kinds of errors generated by MT systems.

This means that effective post-editing of machine-translated texts should never be carried out by anyone who is not an expert in translation; even extensive expertise in the subject matter is not enough to guarantee a high-quality final translation free of any errors which distort the meaning. So using MT does not in any way eliminate the need for highly trained translation experts.

The bottom line

Using free translation tools is a risky business and data protection concerns alone — not to mention issues of quality — mean that there are very few situations in which these tools are suitable for professional translation service providers. They can be helpful for private individuals in certain situations or for certain texts. This includes publicly accessible texts such as press releases or online articles, when the user only wants to understand the gist and doesn’t need every detail to be translated with absolute accuracy. Or texts which would otherwise not be translated at all, such as tourist information.

It would be remiss not to mention more specialised machine translation solutions which require a licence and can be trained in particular subject areas and types of texts. These are mostly used by large technology firms such as Siemens and VW, as well as by the EU institutions. The more standardised the language of the source text, the better the translation can turn out — as long as the machine in question has been fed with huge amounts of correct, subject-specific training data. But these systems aren’t yet suitable for a translation company like Peschel Communications GmbH, since we work on a broad spectrum of texts from different subject areas, including many marketing and advertising texts which require a freer translation style. For technically complex or customer-specific texts, human translations are far superior to post-edited machine translations and much less time-consuming. But we are following the latest developments in this field closely — we certainly want to keep an open mind about the potential that MT technologies might yet offer.

[1] Source: https://gdpr-info.eu/art-4-gdpr/ (Accessed on 21 October 2019)

[2] Source: Abraham de Wolf: Übersetzen mit Software, wer ist der Urheber? [Translating with Software: Who Holds the Copyright?] In: Jörg Porsiel (Ed.): Maschinelle Übersetzung [Machine Translation], Berlin: BDÜ Fachverlag, p. 61 et seq., our translation

[3] Source: https://www.deepl.com/en/privacy.html (Accessed on 21 October 2019)

[4] Source: https://www.microsoft.com/en-gb/servicesagreement/ (Accessed on 21 October 2019)